James Salter knew how to live and how to die. He lived large and died fast.

James Salter knew how to live and how to die. He lived large and died fast.

His sudden passing of a heart attack came as a shock to his friends. But it might well have been plotted by the esteemed novelist, who only two years earlier finally published the most extravagantly praised novel of his famed career, “All That Is.” Salter died at the top of his game.

Only ten days after a celebrating his 90th birthday, a small group of his friends, along with his wife, three grown children, and daughter-in-law, gathered at a graveside in Oakland Cemetery, Sag Harbor’s burial grounds for many writers, editors, and artists.

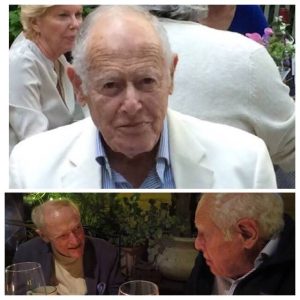

It was hard to believe we were saying goodbye. The photograph of Big Jim below was taken by me this summer, when he was having fun and being toasted by a few friends with martinis he had concocted with his legendary secret sauce. Astonishingly handsome, enviably erect, Salter carried himself with the same courage and attention to form that he brought to each of his life’s endeavors.

The military man was envied by men for having flown 100 combat missions as a fighter pilot in the Korean War. The non-fiction writer was appreciated by editors and flying enthusiasts for translating that rare experience into unforgettable prose. The lifelong skier was legendary for sculpting the snow on thousands of perfect runs down the mountains of Aspen, Colorado. The novelist was adored by his editors, among them, the late Joe Fox at Random House and Robert Emmett Ginna at Little, Brown. The legendary Random House editor, Robert Loomis, also spoke words of praise for Salter at his funeral.

He lived so long that his youngest child, Theo Salter, now 30 and an aspiring writer, who was born when his father was 60, did not know until the funeral that his father started out as a poet. “But I‘ve always felt that his prose was poetic,” Theo told me, “and every sentence was crafted with the care of a poet.”

Although Salter was never a big commercial success, he was lavishly admired by anyone who appreciated the imagination that could produce holistic characters and sentences of literary fiction that embedded in the brain like perfectly cut diamonds.

He recalled recently that he has often been asked: “What’s it like to be so old?” He told friends, “It’s a great relief.”

At Salter’s funeral yesterday, Bob Ginna recalled that a poetic sensibility informed all of Jim’s writing. “He was tireless and fastidious in weighing each word before it went into print, bent on excellence.”

In that connection, Ginna quoted Hesiod, the Greek poet of the seventh century BC: “Before the gates of excellence the gods have placed much sweat. Long is the road there to, steep and twisting, but when the top is reached there is peace.”

Salter and Ginna spent many evenings over oysters and martinis, sharing their favorite quotations from German poets such as Rilke and Goethe. Ginna concluded his remarks with Goethe’s haunting “Wanderer’s Nightsong,” that he thought appropriate to the setting. He translated the lines as “Over all of the peaks/ there is a stillness,/ in all the treetops/ hardly a breath stirs;/ the birds are falling asleep in the forest./Only wait;/ soon, you too shall rest.”

In his last couplet, Goethe is saying to the traveler who contemplates the vista before him, “Patience. You, too, will know peace.”

0 Comments